Permanent Removal vs. Resignation

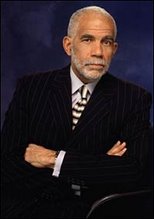

Citing his superior understanding of the law and concern for legal issues, Durham County Senior Resident Superior Court Judge Orlando Hudson continued yesterday's hearing on the removal of Mike Nifong from the office of Durham County District Attorney until Monday in order to allow the disgraced DA the opportunity to resign from office after the end of the State's fiscal year.Ironically, the complex legal issues extending beyond the comprehension of mere Durham citizens that Judge Hudson refers to were raised by his own apparent failure to allow Mr. Nifong sufficient notice of yesterday's hearing.“What justice requires is that the legal process be correctly followed…There is some question as to what kind of service is required to be had …by Mr. Nifong for this particular hearing. That is one of the concerns of the court…I understand the concern of the people…And that may be [one final insult to the citizens of Durham County]. But, I can’t make decisions based on what the people of Durham County think of Mr. Nifong. I have to make it based on what I perceive there being a legal issue. There’s a legal issue. I’ve reviewed this. I understand what Mr. Zaytoun is talking about… I understand that there is an issue that can be resolved and that’s going to be resolved either way. I’m perfectly satisfied that I can proceed as Mr. Zaytoun has said. But I need to head off things that will be a tremendous problem for me in the legal system and the public is not going to understand that. I don’t expect everybody in the public to be a lawyer and to understand the legal issues. That’s what I’m supposed to know. That’s what I’m supposed to do.” WRAL Hearing Video

On Monday, a deputy sheriff tried to serve notice of the hearing at Nifong's house, but he wasn't there. His wife, Cy Gurney, wouldn't accept the paperwork, Hudson said. So the deputy posted the notice on Nifong's door.

Some legal observers suggested Wednesday that leaving the notice on a door was insufficient, since the law requires serving Nifong in person. The

same observers said the notices must be delivered at least 10 days before a scheduled hearing. Nifong's was left at his house three days in advance."He clearly did not get the required statutory notice," said veteran Durham lawyer Tom Loflin. "Even if sticking it on his door was adequate, which I highly doubt, the length of notice was not sufficient. The hearing will be a nullity. Should Nifong appeal, whatever happens is subject to reversal." Herald-Sun

Judge Hudson's newfound appreciation of proper service appears to be a reversal from the astute legal understanding he expressed earlier this week.In further fallout from the Duke lacrosse sex-offense case, former District

Attorney Mike Nifong will undergo a civil removal hearing on Thursday unless he accelerates his projected resignation date of July 13, Durham's top judge said Monday.Superior Court Judge Orlando F. Hudson said a deputy sheriff attempted to serve the hearing notice at Nifong's November Drive home Monday evening, but Nifong's wife -- Cy Gurney -- would not accept it.

The deputy then posted the notice on Nifong's door, according to Hudson.

"That's proper service as far as I'm concerned," the judge added. Herald-Sun

Hudson's plans to wait until 11 a.m. Monday to announce whether Nifong would be removed from office upset Betty Tenn Lawrence, the Asheville lawyer representing Brewer in her ouster petition.

Allowing Nifong to leave on his own schedule, Lawrence said, would be "one final insult to the citizens of Durham County."

But Zaytoun offered a different perspective. The rarely used procedure set up by the state legislature, he said, is designed to ensure that rogue prosecutors are removed from office, and a resignation would achieve the same result.

On 1 December 1977 the Judicial Standards Commission, in accordance with its Rule 7 (J.S.C. Rule 7), 283 N.C. 763-770 (1973), notified Respondent that on its own motion it had ordered a preliminary investigation to determine whether formal proceedings should be instituted against him under J.S.C. Rule 8. The notice informed Judge Peoples (1) that the subject of the investigation would be his "alleged misconduct in the handling or disposition of criminal cases in the Ninth Judicial District, including the placing of numerous criminal cases in an inactive file in lieu of disposing of such cases in open court"; (2) that the investigation, reports and proceedings before the Commission would remain confidential as provided in J.S.C. Rule 4; and (3) that he had the right to present to the Commission for consideration "such relevant matter" as he might choose.

Judge Peoples had been a district court judge since 2 December 1968, the date the district court was established in the Ninth Judicial District.

On 10 January 1978 Judge Peoples tendered his resignation as a district court judge to the Governor in the following letter:

"Honorable James B. Hunt, Jr.

Governor of the State of North Carolina

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Dear Governor Hunt:

I hereby submit my resignation as a Judge of District Court for the Ninth Judicial District, State of North Carolina, effective February 1, 1978. I have been honored to serve the people of the District as a District Court Judge and hope to continue to serve them in some other capacity within the Judiciary.

Respectfully,

s/ Linwood T. Peoples"

On 20 January 1978 Governor Hunt accepted Judge Peoples' resignation to be effective on 1 February 1978.

On 30 January 1978 Judge Peoples was served with a formal complaint and notice which informed him (1) that the Commission had concluded "upon the original complaint and the evidence developed by the preliminary investigation" that formal proceedings should be instituted against him; (2) that H. D. Coley, Jr., would act as special counsel for the Commission; (3) that the charges against him were (a) wilful misconduct in office, and (b) conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice that brings the judicial office into disrepute; (4) that the alleged facts upon which the foregoing charges were based are specifically set out in the verified complaint attached to the notice; and (5) that it was his right to file a verified answer to the charges within 20 days.

...

While so far as our research can determine the issue has never arisen in a hearing before a body such as our Judicial Standards Commission, the courts of other jurisdictions have considered the effect of a public official's resignation on a proceeding to remove him from office. If the only purpose of the proceeding is to vacate the office, it has been held that the proceeding becomes moot upon the incumbent's resignation. People ex rel.

But where the statute imposes sanctions in addition to ouster, the proceeding may be prosecuted to its conclusion despite the official's resignation.

In State v. Rose, supra, the Attorney General for the State of Kansas brought an action in quo warranto in the Supreme Court to oust the defendant as Mayor of Kansas City, on the ground that he had purposely violated the State liquor laws. After the trial was completed, but before the court issued its judgment, the city council accepted defendant's resignation.

Shortly after the judgment of ouster, a special election was called to fill the vacancy in the office of mayor. In defiance of the judgment, defendant ran for the office and was elected to serve the balance of his original term. When Rose was cited for contempt, his defense was that the court lacked the power to exclude him from office since he had voluntarily resigned and surrendered the office prior to judgment.

Noting that the purpose of the proceeding was not only to remove Rose from office but also to disqualify him for the remainder of his term, the court held that the proceeding had not been rendered moot by defendant's resignation and found defendant in contempt. It explained its conclusions as follows:

"The violations of law by the officer are not only public offenses but in committing them he forfeits his right to the office, and this forfeiture may be judicially declared in a quo warranto proceeding. The judgment cannot be deemed to be invalid because of the resignation of Rose just before its rendition. The issues were joined, testimony had been taken, and the case was ripe for trial before the resignation, and the defendant could not then, by surrendering the office divest the court of jurisdiction, nor thwart the purposes of the proceeding. The public had an interest in the action, and the judgment to be rendered was of no less consequence to it than to the individual interests of the defendant."

...

If G.S. 7A-376 limited the sanctions for wilful misconduct in office to censure or removal, Respondent's resignation would have rendered the proceedings moot. The statute, however, envisions not one but three remedies against a judge who engages in serious misconduct justifying his removal: loss of present office, disqualification from future judicial office, and loss of retirement benefits. Only the first of these was rendered moot by Respondent's resignation.

...

Disqualification from office has long accompanied removal for misconduct under the impeachment provisions of both the state and federal constitutions. See, e.g., N.C. Const. of 1835, Art. 3, § 1. We do not believe that the legislature misconstrued the spirit of the amendment when it attached this same consequence to removal proceedings under G.S. 7A-376. The drafters of the impeachment provisions of the Constitution recognized that the removal of a public official for wilful misconduct in office without disqualifying him from future office might well be a futile gesture. In the absence of such a provision a judge who had been removed for wilful misconduct in office could not only run for election to fill out the term from which he had been removed but also -- as here -- seek higher judicial office. Such an event would obviously thwart the purpose of the removal proceedings, which is to protect the public from unfit public officials.

...

As an alternative ground for our holding that the North Carolina Constitution authorizes the General Assembly to prescribe disqualification from office as a consequence of removal under G.S. 7A-376, we note the language of Article VI, Section 8 of the Constitution, which provides as follows:

"Sec. 8. Disqualifications for office. The following persons shall be disqualified for office: "First, any person who shall deny the being of Almighty God. "Second, with respect to any office that is filled by election by the people, any person who is not qualified to vote in an election for that office. "Third, any person who has been adjudged guilty of treason or any other felony against this State or the United States, or any person who has been adjudged guilty of a felony in another state that also would be a felony if it had been committed in this State, or any person who has been adjudged guilty of corruption or malpractice in any office, or any person who has been removed by impeachment from any office, and who has not been restored to the rights of citizenship in the manner prescribed by law." (Emphasis added.)

...

For the reasons enunciated in this opinion it is ordered by the SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA, in conference on 29 December 1978, that Respondent Linwood Taylor Peoples be and he is hereby officially removed from office as a judge in the General Court of Justice, District Court Division, Ninth Judicial District, for the wilful misconduct in office specified in the findings of fact made by the North Carolina Judicial Standards Commission, which findings the Court has adopted as its own.

In consequence of his removal, Respondent is disqualified from holding further judicial office and is, therefore, ineligible to take the oath of office as the resident Superior Court Judge of the Ninth Judicial District, the office to which he was elected on 7 November 1978 and certified by the State Board of Elections on 28 November 1978. For the same reason he is ineligible for retirement benefits.

2 comments:

Removal from position, in instances of illegal actions, should and usually do, result in prosecution of those actions, in addition to that removal.

The actions of Judge Hudson are batantly putting on display the cronyism inherent in the legal system. His claim that I do not understand the law as well as he may be correct, to an extent; but his detailed knowledge is being used to manipulate and to circumvent; not enforce the law. That much, I understand.

I would like to see the judge's sworn statement that he did not counsel Nifong to "disappear" in order to avoid service. The action and timing was just too convenient for Nifong and to the obvious aims of the judge.

I am grateful that respect cannont be legislated...

what a great comment posted above.

I am also very grateful to LieStoppers for once again being on top of things and showing us why the resignation should not have mattered.

Post a Comment